EYE ATTACK

Op Art and Kinetic Art 1950-1970

4.2.2016 – 5.6.2016

Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark

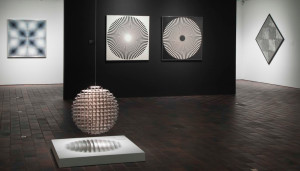

Louisiana’s spring exhibition is the first major presentation of Op Art and Kinetic Art in Scandinavia for more than 50 years and takes a closer look at one of the most innovative currents in the period 1950-1970, which still leaves its marks on the art and visual culture of today. The exhibition shows works from museums and collections in Europe and the USA, but takes its point of departure in Louisiana’s own collection, which features important works by the main figures of the movement, including several works that have only rarely – or never – been on show at the museum.

With around 100 works by 40 artists, among them major names like Hungarian-French Victor Vasarely (1906-1997), British Bridget Riley (*1931), French François Morellet (*1926), Argentinean Julio Le Parc (*1928), Italian Gianni Colombo (1937-1993), Venezuelan Jesús Rafael Soto (1923-2005) and Carlos Cruz-Diez (*1923), the exhibition opens the door on a visual experimental laboratory with a broad spectrum of media paintings, reliefs, objects, mobile sculptures, light-works and large ‘environments’.

Eye Attack turns the focus on a current in twentieth-century visual art that deliberately targets our sensory apparatus; art which seductively and unsettlingly wants to attack the cool overview by confusing and irritating the eye with optical illusions and artworks that cultivate ‘motion’.

Some images consist quite simply of black and white lines. But the lines are arranged such that the simplicity becomes complex the instant the images reach our eyes. The sense of vision is irritated, the eye is manipulated, images spin and jangle. Willy-nilly, our eyes are caught in the optical play of the works. This is not a matter of experiencing a sensitive artist’s perception of the world, but of placing the senses of the viewer – yours and mine – at the centre.

“Op Art” is an abbreviation of Optical Art. It is an avant-garde movement that had its breakthrough in the mid-1950s as an extension of abstract, constructivist art. The current had its glory days in the 1960s – side by side with the many other experimental new departures of the decade – and established itself internationally across widely differing political and cultural boundaries. “Kinetic Art” is a catch-all term for artworks that cultivate motion. This may be in the form of illusion, as in Op Art, or it may be actual physical motion, as in sculptures with motorized parts.

Kinetic and optical art go hand in hand and make up a field of varied expression that shares a geometrical formal idiom without narrative content, as well as the use of new, industrial materials and techniques and the cultivation of motion and the direct sensory impression. The viewer is placed at the centre as an active player in the artistic process in a showdown with the static, autonomous work of art.

The artists were concerned with objectivity, science and the psychology of perception. They were inspired by the technological advances of the epoch and a ‘cool’ industrial aesthetic – quite contrary to the more emotionally-driven, spontaneous currents of the time such as Abstract Expressionism and Informal Painting, and unlike the messier Fluxus movement and figurative Pop Art.

Kinetic and optical art are the products of a particular era and are typified by a modern experience of the flickering mutability of everything, by the dissolution of the established, fixed points of reference in the understanding of the world, and by the artists’ efforts to make art democratic and outward-looking. The last of these aspirations was in fact emphatically successful, for rarely have mass culture, fashion and advertising so warmly welcomed a new aesthetic approach. Suddenly, there was “Op” on everything – from dresses, record covers and pillboxes to jigsaw puzzles.

The aesthetic results of the movement are surprisingly timeless. The works still appeal directly to the eye today with a mixture of instant fascination and nostalgia. The current has furthermore left clear marks in today’s visual art and culture, in which many artists are working with the direct activation of our senses, and where – not least in the computer graphics and games of the digital world – there is an abundance of illusionism and Op aesthetics.

The exhibition

Eye Attack is being shown in the West Wing of the museum. The first section of the exhibition consists of monochrome and black-and-white works. Fundamentally, one does not need colour to create optical

illusions or dynamic surfaces, and many artists therefore worked in black-and-white to perfect and maximize the optical effects with the starkest possible contrast. In this section, we also find other typical

characteristics and devices of the movement: geometry and systematization; all-over patterning and the use of single elements which in repetitions and displacements create dynamic surfaces and eye-stressing effects that are easy to experience but hard to analyse; a pre-digital pixel aesthetic; modern materials such as plastic, aluminium and plexiglass, and on the whole surfaces that are devoid of traces of the artist’s hand.

Further on in the exhibition one finds works that use optical effects with and in colour, and – in an extension of the whole colour and perception research of the history of painting, not least from the Impressionists on – create illusions of space and motion with colour contrasts that clash with one another, or with tonal or chromatic slippage and exploitation of the ‘values’ and visual energies assigned to colours in our perception.

Two of the quite central artists are spotlighted with a larger number of works: Hungarian-French Victor Vasarely (1906-1997) and British Bridget Riley (b. 1931). Both have been pioneers in the development and dissemination of perceptual art (as Op Art is also called). Both artists first cultivated the optical effects in black-and-white paintings and then continued their explorations of our visual perception in colour, and both have worked with the repetition of relatively simple elements – for example squares or lines – which in carefully arranged displacements create illusions of space and motion.

Vasarely is often called “the father of Op Art” and was the pioneer not only of number of formal devices but also of the ideal of creating art that is open and accessible to all and which has our experience – the experience of the viewer – as the main interest. Riley forces the eyes and thus the brain on extreme ‘overtime’ in the optical play of stability/instability and surface/space. The works go directly to the core of our perceptual apparatus and make us experience phenomena that are ‘not there’, but arise as derivative effects in the brain’s processing of the visual impression, for example, rhythmically throbbing movements and phantom colours between the black lines.

In an attempt to expand the traditional concepts of painting and sculpture, many artists worked with

three-dimensional reliefs, of which the exhibition shows examples by among others Soto and Cruz-Diez. Some people will be familiar with Soto’s works, where thin sticks hang in front of painted surfaces, from

Louisiana’s collection. He makes particular use of the moiré effect that arises when lines or patterns are superimposed and displaced. Cruz-Diez’ works are built up of coloured slats and change character depending on the angle they are seen from.

The interaction between work and viewer culminates in large spatial installations, so-called environments – a format that the optical-kinetic current was early to explore in its efforts to create a new kind of viewer-involving and accessible art. The exhibition begins by presenting a wall with flickering colour pixels (Morellet); then two environments with space-confusing arrangements of elastic cords and mirrors (Colombo and Le Parc); a space with flash-like neon lights that create after-images (Morellet) and finally a universe of light and colour (Cruz-Diez) in one of the museum’s glass corridors.

‘Motion’ is a code word in this exhibition, and in its concluding section there are a number of motorized reliefs and sculptures. Here too, we see the experiments of the movement with hybrid formats, materials and techniques, and the works resemble strange machines without many traces of the monumentality and solidity of old-fashioned sculpture. Several works incorporate electric light – as a new energy and a dynamic element that fills our gaze as well as the surrounding space with light and shadow effects.

Op Art and kinetic art wanted to put art ‘in synch’ with the modern, dynamic age and to point to our dynamic, manipulable perception as a co-creating factor in our experience of the world. Eye Attack presents works that are concerned with how we see and with the connections between the world and our senses.

0 Comments